Written by Elizabeth Clarkson, Ed.D

If you’ve ever spent a day in an early childhood classroom, you know traditional reading, writing, and math skills aren’t the only thing happening. In fact, you might have been overwhelmed by all the movement and activity! Teachers of young children know that learning at this age is active, sometimes loud, and is happening all over the room. If teachers are going to plan intentionally in this type of unique learning space, they will need to consider all the various elements of learning at this age and the different options to organize and share this information with others.

Sneak Peak: How do we capture non-thematic elements in our maps, including language and literacy development, phonological awareness, and social-emotional development? Keep reading!

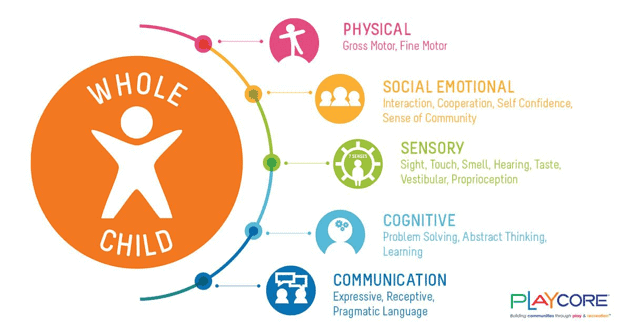

Although most teachers are planning with some type of thematic structure in mind, there are also many critical learning elements that are non-thematic in nature that need significant attention too! Within cognitive areas like language and literacy, there are foundational skills, such as phonological awareness, that are essential to develop before traditional reading occurs. Non-cognitive elements such as social-emotional development, approaches to learning, and large and fine motor skills are all integrated into a high quality early learning classroom. The graphic above is one illustration of the variety of areas in learning in which teachers must be aware and take into consideration while considering the whole child. Teachers would have an endless list of skills and mindsets in their written curriculum if they tried to include everything young children are learning. So the question is: If a teacher plans and organizes the year in thematic units, where does everything go in a curriculum map?!

Although most teachers are planning with some type of thematic structure in mind, there are also many critical learning elements that are non-thematic in nature that need significant attention too! Within cognitive areas like language and literacy, there are foundational skills, such as phonological awareness, that are essential to develop before traditional reading occurs. Non-cognitive elements such as social-emotional development, approaches to learning, and large and fine motor skills are all integrated into a high quality early learning classroom. The graphic above is one illustration of the variety of areas in learning in which teachers must be aware and take into consideration while considering the whole child. Teachers would have an endless list of skills and mindsets in their written curriculum if they tried to include everything young children are learning. So the question is: If a teacher plans and organizes the year in thematic units, where does everything go in a curriculum map?!

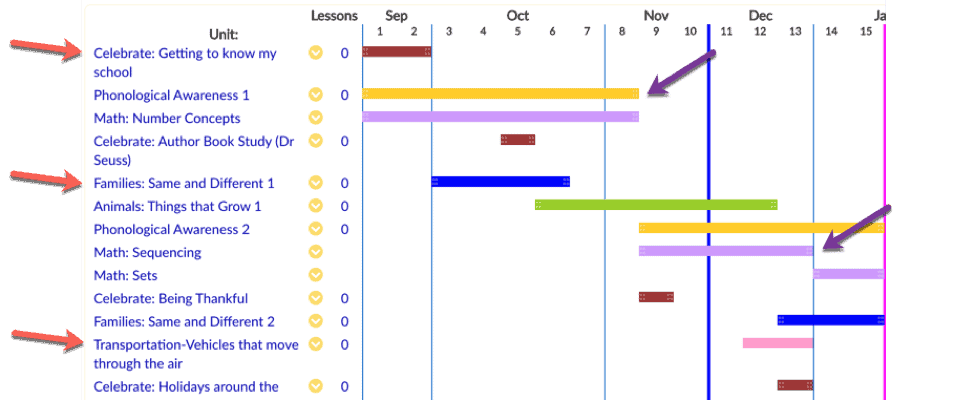

Language and Literacy: Consider a full year calendar that includes units/topics, as well as other useful chunks of information such as phonological awareness or mathematical thinking. Inside each unit or topic, the information is related to that specific content (i.e. transportation, plants, friendship, etc.) How can a teacher also manage these other elements?

There are several options. As one option, let’s consider mapping using a single “integrated” course. In the image above, you’ll notice the red arrows point out the thematic units. The purple arrows are phonological awareness and mathematical thinking foundational skills that have their own sequential timeline, but are not thematically related. It doesn’t mean a teacher can’t connect and use the themes and foundations skills together. For some teachers, it might be helpful to map them as separate “units,” so he/she can think about them individually without being overwhelmed.

Phonological Awareness: Let’s think specifically about areas such as phonological awareness. These early language and literacy skills are certainly critical as foundational pieces of long term academic success. Phonological and phonetic skills, for example, are sequential in nature, but do not need to be taught to mastery before moving to the next skills. These skills are organized into sub-groups and children are more successful when they are provided multiple opportunities over long periods of time to explore, investigate, and play in no stress situations with sounds, letters, and combinations of the two. They are related to each other, but not necessarily to any particular thematic units.

By organizing them into larger blocks of time over multiple units, a teacher is able to provide experiences in multiple contexts and allow for the necessary time it takes for children to be exposed to, become familiar with, and eventually use these skills independently.

For clarity's sake, it’s important to note than phonological and phonetic awareness and eventually phonics are skills learned over several years. We are suggesting one way to initially organize this information in a single year and course. All early childhood teachers should be responsive and respectful of individual children’s approach and pace of learning.

Social-Emotional Learning: Let’s switch gears and think about a few non-cognitive elements in planning.

Social-Emotional Learning: Let’s switch gears and think about a few non-cognitive elements in planning.

The graphic to the left is one of many possible visual examples of social and emotional learning, breaking this type of learning into five sections. Although driven from developmentally and age appropriate expectations, all schools will define and articulate social-emotional learning in similar but unique ways. The many different areas of social-emotional learning emphasize how large a part of early childhood these elements are. Ask any early childhood teacher; this category is equally important to cognitive growth, with many teachers arguing that it should be the main focus of an early childhood program!

Most programs have social-emotional benchmarks and goals too. If teachers listed every single time children practiced “turn taking” or “using creative ways to solve a problem independently,” where would they ever stop? The same thinking applies to categories such as approaches to learning and fine and gross motor skills.

We agree these categories are super important, but how can a teacher fit all the different social-emotional elements into a curriculum or unit map? Maybe the answer is, “remember the purpose of your unit map.” A unit map should help organize that unit’s specific information, not be a written collection of a year’s worth of information.

As we’ve established, social skills are practiced all year during all experiences. Are there certain moments/topics or planned activities that make sense to stop and talk about a specific skill and in an intentional way? If so, feel free to include that in a unit map or lesson plan to draw attention to the moment. If the information is more general and will be practiced over a longer period of time, consider other places (website, handbooks, mission/vision statements, published documents from the school) that can include this type of information so teachers are paying attention to them as a whole set, not as individual items per week.

Just like children, schools and classrooms are unique. By having a shared conversation around ways to organize all the different elements that are important in an early childhood classroom, schools can decide how to use a unit map most effectively for thematic and non-thematic content, as well as consider other relevant elements from an early childhood perspective.

For more information on the topic, including a unit example, check out our blog “Moving from Lesson Planning to Unit Planning in Early Childhood Classrooms!”

Dr. Elizabeth Clarkson began her career in North Carolina public schools. After living in several other countries, she now considers North Carolina her home again. She has worked as a teacher, literacy coach, and principal in public and private schools in the United States, Ecuador, and Brazil. She combines her experiences in schools and nonprofit education to view all education conversations within the larger context of community, its values, and influences. She continues to draw from her experiences in academic coaching and international living to support schools in developing strong curriculum processes that support their unique values and identities.

Dr. Elizabeth Clarkson began her career in North Carolina public schools. After living in several other countries, she now considers North Carolina her home again. She has worked as a teacher, literacy coach, and principal in public and private schools in the United States, Ecuador, and Brazil. She combines her experiences in schools and nonprofit education to view all education conversations within the larger context of community, its values, and influences. She continues to draw from her experiences in academic coaching and international living to support schools in developing strong curriculum processes that support their unique values and identities.